By Robert Kittle

South Carolina taxpayers recently spent almost $237,000 to build two new guard towers at Lee Correctional in Bishopville, not just to prevent inmates from getting out but also to keep contraband like drugs and cell phones from getting in. Prison officials say people throw contraband over the fences to inmates inside.

The prison also has a camera network, including new thermal cameras to spot someone’s body heat in the dark, at a cost of more than $2.2 million.

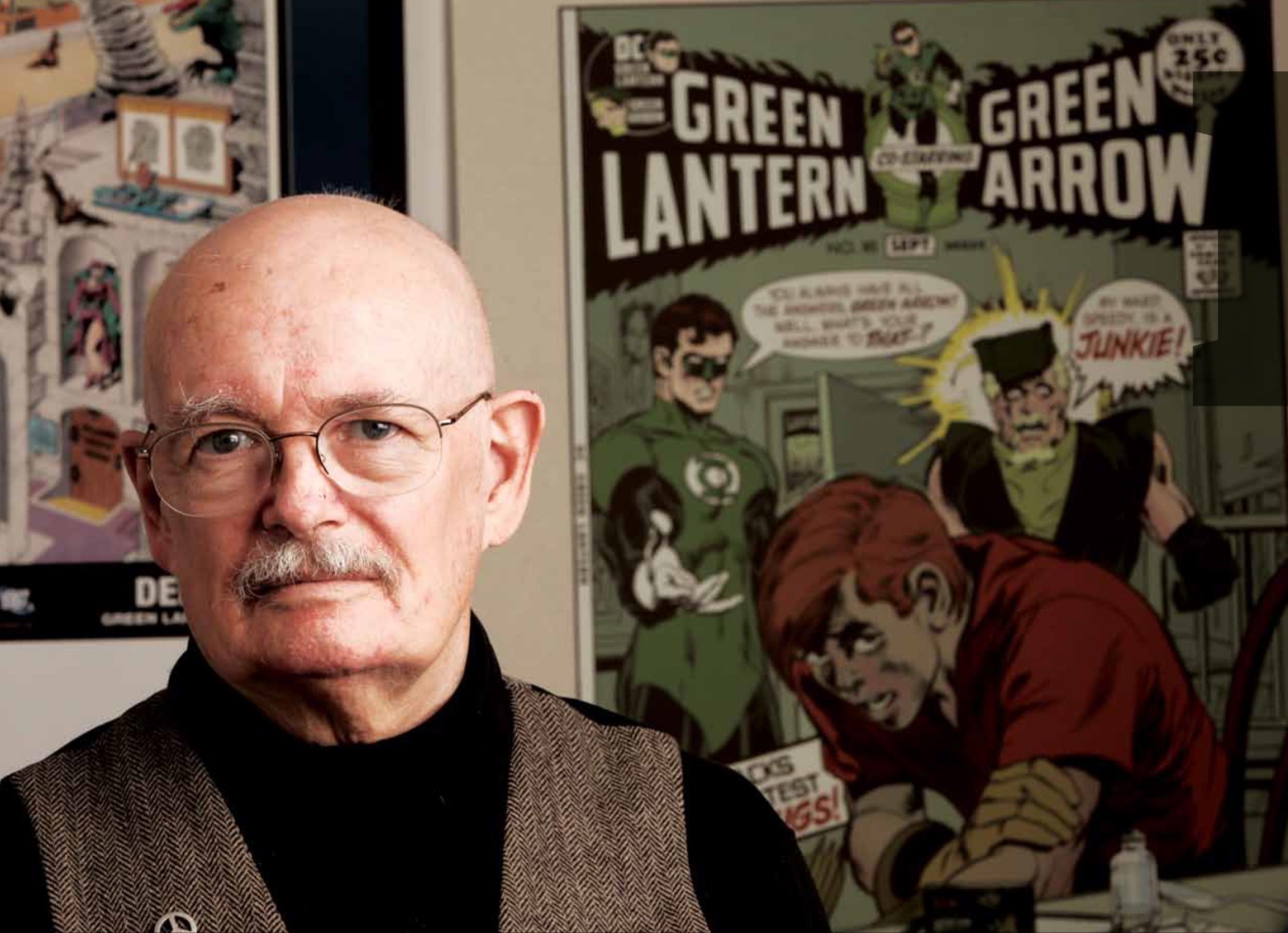

Robert Johnson can tell you why it’s so important to keep cell phones out of the hands of inmates. He used to be the captain in charge of finding contraband at Lee. An inmate inside the prison used an illegal cell phone to order a hit on Johnson.

Around 5:30 on the morning of March 5, 2010, Johnson was getting ready for work when he heard someone bust in the front door to his home. Johnson says he knew there was a price on his head but thought he would be attacked in the prison.

His wife was still asleep in the bedroom close to the door, so Johnson called out to draw the man to him and away from his wife. Johnson came out of the bathroom and the man came at him in the hallway.

“And we struggled,” Johnson says. “He was a much bigger guy, and he was able to push me away. And the last thing I remember is a gun coming up. And he shot me. Next thing I know I was on the floor in the bathroom.”

He had been shot six times in the chest with a .38 caliber pistol.

He was rushed to a hospital in Sumter where they tried to slow down the bleeding and then he was airlifted to the trauma center at Palmetto Richland in Columbia.

“Three times I bled out,” he says. “And they were about to give up. So my wife, they kept telling my wife, ‘He’s not gonna make it. He’s not gonna make it. He’s gonna die. He’s gonna die.’ And she just said, ‘God will get a handle on the bleeding.'”

His doctor allowed his wife to come into the operating room, with no gown or mask on, because he was sure Johnson was going to die and he wanted her to be able to say goodbye. She kissed him and prayed for him.

It took 63 units of blood and hours of surgery to save his life. He’s still facing another surgery next month and has permanent nerve damage in one leg. He needs a brace on his foot and a cane to walk.

He thinks the new guard towers at the prison will help slow down contraband, but won’t stop it. “This just makes them work harder. They’re still going to have cell phones. But with the block, the cell phone blocking, that’s a wrap. It would completely close it.”

He favors jamming technology that blocks cell phone signals within a prison but not outside its walls. The Department of Corrections demonstrated the technology inside a prison in 2008, showing that cell signals inside a prison building were blocked but cell reception outside the buildings was not affected.

The price of the jammers is vague, since they’re illegal right now, but the estimate is about $30,000 per building, which would be less than the new guard towers cost.

The Federal Communications Commission won’t allow prisons to use the jamming technology, citing the 1934 Communications Act, which prohibits the intentional disruption of radio signals.

It will allow something called managed access. Some states, including Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and California are trying it.

Under managed access, a prison puts a cell tower inside, or close to, a prison, creating a virtual umbrella over the prison. All cell phone calls in the area go through that tower. Any unauthorized calls, like those from prison inmates, get blocked, while authorized calls go through. The drawback is that businesses or anyone living close the prison has to register their cell phones to get authorized so their calls go through. Cell phone providers also have to cooperate because the managed access tower has to be able to handle all the carriers’ signals.

Cost is another factor, with managed access running anywhere from $400,000 to $1 million per prison.

SC Department of Corrections director Bryan Stirling says it’s frustrating that the FCC won’t allow cell phone jamming, since it would be cheaper and more effective than new guard towers.

“This is just one measure amongst many that we’re using at our institutions across the state to make them safer, but it’s not the catch-all. Blocking, I believe, would be a catch-all that would stop them from being able to reach on the outside and talk on the outside and continue their criminal ways,” he says.

While the FCC says the 1934 Communications Act prohibits cell phone jamming, the actual wording of the law, in section 333, says, “No person shall willfully or maliciously interfere with or cause interference to any radio communications of any station licensed or authorized by or under this chapter or operated by the United States Government.” A prison inmate using a cell phone is not an authorized radio communication. And while the FCC uses that section to justify not allowing prison cell phone jamming, another federal agency, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, does allow the jamming of unauthorized radio signals.

The FCC says it won’t allow cell phone jamming in prisons because it’s illegal and because it would interfere with 9-1-1 and other emergency calls, and it might interfere with the legitimate cell phone calls of businesses and people who live near prisons. The Department of Corrections says its prisons are far enough away from homes and businesses that a jamming signal inside a prison would not interfere with legitimate cell phone use outside.