SAN JUAN, Texas (Border Report) — Miles from the nearest town, over a dusty, caliche rock levee road that winds as close to the Rio Grande as the mesquite trees and prickly pear cactus will allow, several members and supporters of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas have been camping at a historic cemetery since January in hopes of preventing the federal government from building a border wall through the gravesites.

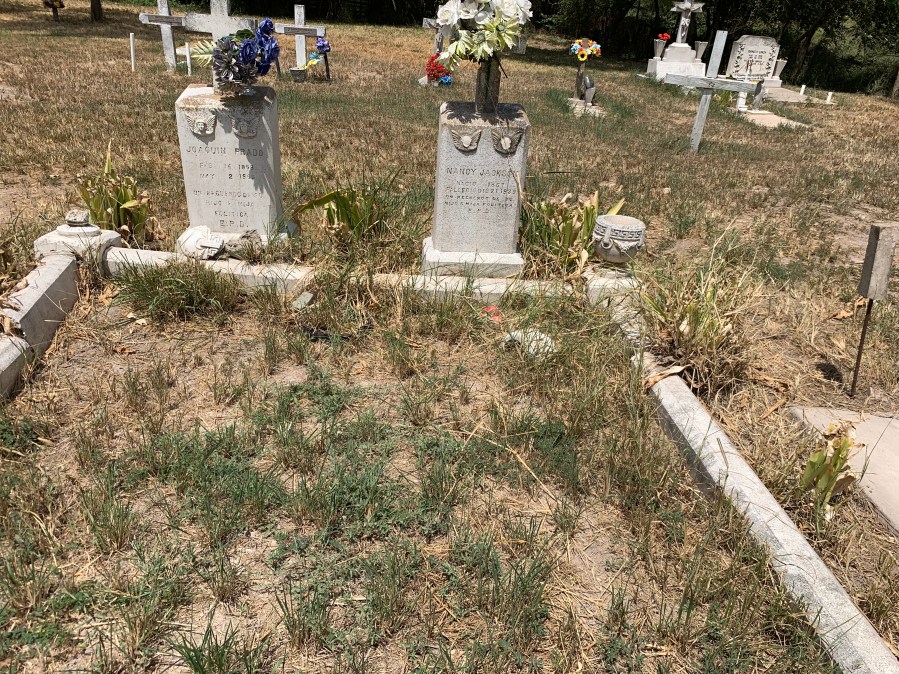

Fifty to 150 graves are located at the historic Eli Jackson Cemetery, which is in such a remote location that most Internet maps refer to it by longitude and latitude coordinates. Many of the remains, which date back to the 1800s and are in unmarked graves, belong to members of the tribe, as well as emancipated slaves.

Signs at the entrance to the encampment called “Yalui Village,” read: “This is Sacred Ground,” and “Human Remains are Human! … Respect Them.”

Despite searing 100-degree temperatures on Wednesday, two supporters of the Carrizo/Comecrudo tribe diligently watched guard over the area. They did not want to be photographed or quoted “for security reasons,” but they did allow Border Report onto the property and gave this reporter a tour and allowed photos.

Tribal spokeswoman Ruth Garcia told Border Report that for the past seven months, someone has always been at the camp maintaining a vigil because they cannot allow their “sacred” cemetery to be destroyed by the border wall.

“We have ancestors who are buried there, some in unmarked graves but it’s mainly the desecration of our lands we are fighting,” Garcia said via phone.

On Aug 7, U.S. Customs and Border Protection announced a construction contract worth up to $304 million to a New Mexico company to build 11 miles of border wall in Hidalgo County, which would cut right through the Eli Jackson Cemetery.

Congress has appropriated billions of dollars of funding for a controversial wall on the Southwest border, which has been a priority of the Trump Administration.

But during a visit to South Texas on Sunday by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi,(D-California), and 12 other members of Congress, U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar, (D-Texas), announced that they were working to exempt Eli Jackson Cemetery and other historic cemeteries that might be in the path of the proposed border wall.

‘We won’t put a fence on that’

“If you remember earlier this year, we were able to stop the fence in SpaceX, Bentsen State Park, the Santa Ana Wildlife, the National Butterfly Center, and the (La Lomita) Chapel where we went to pray today,” Cuellar said on Sunday as the delegation held a news conference at the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen. “Our intent now is to add a sixth area and that is to include the historical cemeteries, like Jackson Cemetery, to make sure they aren’t included so we won’t put a fence on that.”

Congress deemed the areas mentioned by Cuellar exempt from a wall built after much public outcry to save those spots.

But Garcia, upon learning that Cuellar has vowed to help spare Eli Jackson Cemetery, doubted lawmakers were trying to help them.

“I don’t believe him,” she said.

Garcia said that despite repeated requests by tribal leaders, lawmakers have refused to meet with them or address their concerns.

“We have a pending lawsuit against the Trump Administration and the different entities involved in building the border wall because of the lack of responses we have been getting.” said Garcia, who is a tribal member.

Historic chapel helped to hide slaves

The lawsuit also names to protect the nearby historic Jackson Chapel, “which was used as a decoy to help the freed slaves through the Underground Railroad to help them come into Mexico,” Garcia said.

According to several published reports, the area was founded by Nathaniel Jackson, the white son of a plantation owner who married an emancipated slave, Matilda Hicks, with whom he spent his life helping other slaves cross into freedom. The interracial couple, along with their eldest son Eli Jackson and six other children, fled from Alabama to the banks of the Rio Grande because they were being persecuted under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Nathaniel Jackson died in 1865. His grandson Elias Jackson’s marker still stands at the Eli Jackson Cemetery today, although there is no headstone. Tribal watchers told Border Report that Jackson family members have identified the marker and they come often to clean and tend to the graves of their family members.

Construction plans for the border wall along the Southwest border of the United States call for a 150-foot enforcement zone surrounding the wall, which would include roads, lighting and cameras.

The wall in Hidalgo County is slated to be built on dirt levees that meander along the Rio Grande and were constructed to help with flooding. The dirt levee is located on a rise just behind Eli Jackson Cemetery. When factoring in the enforcement zone, many of the graves at the cemetery would be destroyed unless it is exempt by lawmakers.

“Our medicines are there. There is a tree there related to our people. We don’t believe that there should be so much genocide going on, the desecration of the bodies. They’re just not respecting our lands,” Garcia said.

LATEST NEWS: