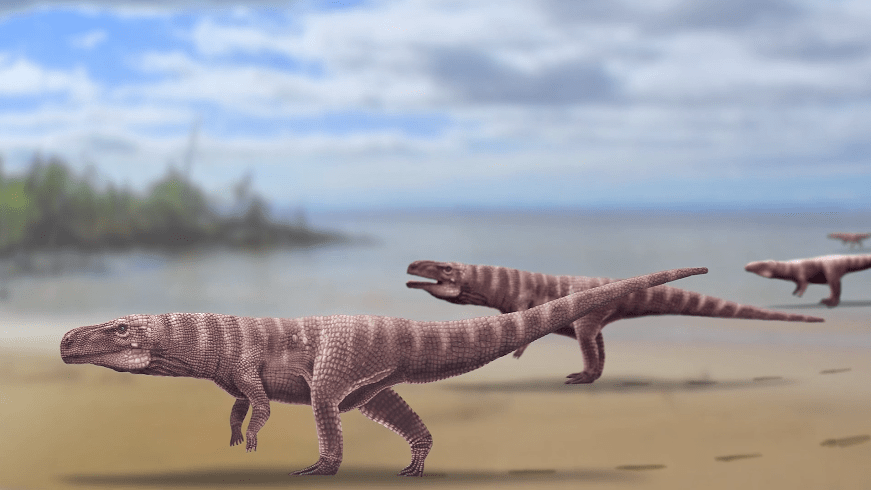

The climate is changing, and so are the turtles.

A study published Monday in the journal Current Biology about green sea turtles that nest along island beaches near Australia’s Great Barrier Reef found that turtles born in areas most heated by climate change are 99.8 percent female. Turtles born farther south, along a cooler beach, are only about 65 percent female.

The result isn’t surprising if you know a bit about turtle biology, but it is alarming. Sea turtles, like these green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), don’t have genetically determined sexes, the way mammals do. Instead, the researchers wrote, “In sea turtles, cooler temperatures produce more male hatchlings while warmer temperatures produce more females.”

An egg in hot sand is more likely to produce a female turtle, and an egg in cool sand is more likely to produce a male.

The pivot temperature where a population will turn out 50 percent females and 50 percent males is based on genetics and varies with species and even individual nesting groups, the researchers wrote. Turtles seem to target their breeding periods to times when the sand is slightly warmer than their pivot temperatures, resulting in populations moderately skewed female. But shift the temperature of that period just a few degrees and the resulting baby turtles will be not just a bit female — instead, hardly a male will appear in the whole group.

Due to climate change, Raine Island — the site of the key breeding ground in this study — has warmed significantly since the 1990s, the researchers wrote, likely accounting for the hard female skew.

So, the researchers developed a new technique: Studying the turtles’ hormones.Proving that the increasing temperatures actually changed the turtle population proved challenging, though. Turtles don’t wear signs of their sex as obviously as humans; researchers can’t tell just by looking between their legs. And the easiest method — cutting them open — isn’t really an ethical way to approach an endangered turtle population.

A genetic test won’t offer any insight into a given turtle’s sex, since sea turtles don’t carry their sexes in their genetic code. But the researchers found that if they brought blood plasma samples back to their lab, they could use hormonal differences to distinguish male and female turtles.

It’s not clear yet, the researcher wrote, how exactly the wild female swing will impact the sea turtles’ future. Males breed far more often than females, but researchers don’t know to what extent the handful remaining can make up for all their missing brothers. It’s also possible, the researchers wrote, that females will seek out mates in cooler climates to the south.

“Our study highlights the need for immediate management strategies aimed at lowering incubation temperatures at key rookeries,” the researchers wrote, “to boost the ability of local turtle populations to adapt to the changing environment and avoid a population collapse — or even extinction.”